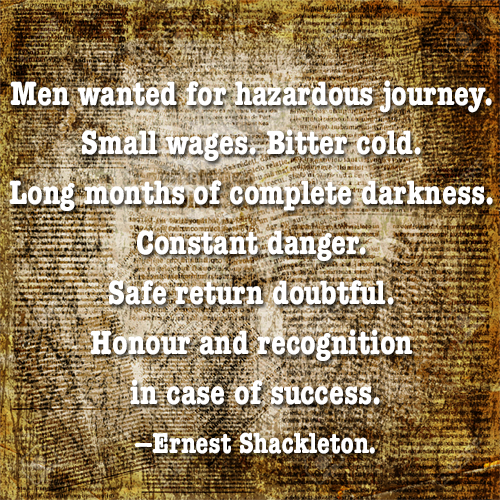

Depending on the context and what we’re going to explore, one of my favorite executive case studies has to do with Sir Ernest Shackleton and the voyage of the Endurance. It is a deep and rich mine of executive discovery opportunities. This year is the 100th anniversary of the conclusion of the Endurance adventure.

The Big Picture

In late 1914, celebrated polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, leader of the British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, set sail with a 27-man crew intending to transverse the Antarctic continent by dog sledge.

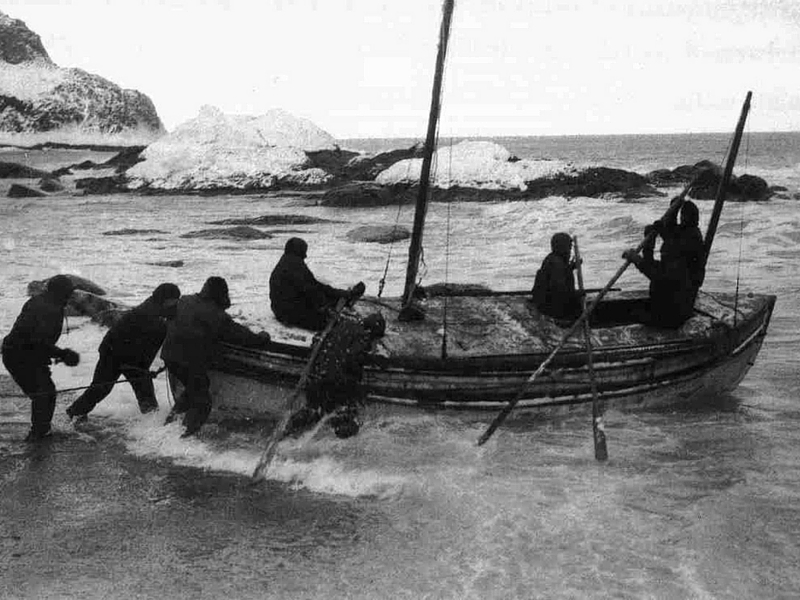

In December of that year, the expedition, aboard the purpose-built polar exploration ship Endurance, entered the pack ice of the Weddell Sea off the coast of Antarctica. The ship was beset and eventually crushed by ice floes in the Weddell Sea leaving the men stranded on the pack ice. All in all, the crew drifted on the ice for just over a year. They were able to launch their boats and somehow managed to land them safely on Elephant Island. Shackleton then led a crew of five aboard a small boat, the James Caird through the Drake Passage and miraculously reached South Georgia Island 650 nautical miles away. He then took two of those men on the first successful overland crossing of the island. Three months later he was finally able to rescue the remaining crew members they had left behind on Elephant Island. Incredibly, the ill-fated voyage did not lose a single man.

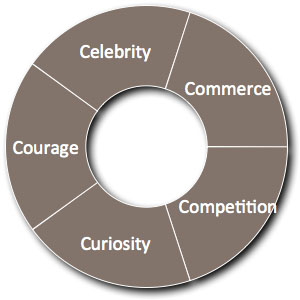

Commerce

While commerce was not the stated goal of this expedition, it would be disingenuous to forget that whale oil was still an important part of the economy during the 1900’s and whalers were interested in discovering new hunting areas. For lighting, whale oil competed and coexisted with camphene (a combination of alcohol, turpentine and camphor oil), lard oil, coal oil and kerosene, even though whale oil was more valuable as a lubricant during the industrial revolution. Furthermore, just as the “space race” generated commercial innovations during the late 20th century in the United States, the “expedition industry” filled a similar role in the late 19th and early 20th century Britain. These expeditions also needed scientific legitimacy to raise the necessary funding.

Curiosity

This was the age of exploration. The Royal Geographical Society (RGS) was founded in London in 1830, and encouraged the advancement of geographic and scientific knowledge by promoting and funding expeditions to Africa, Asia, the Arctic, and the Antarctic. As one society member explained in a history of the organization published in 1917:

. . . the main function of the

Competition

At the time of Shackleton’s appointment to the National Antarctic Expedition (NAE) in 1901, Britain was one of many nations engaged in a fierce competition to be the first to reach the South Pole and claim it under the nation’s flag. Britain had held records for the northernmost and southernmost points reached by boat. Explorers from Norway, Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden, and other nations were also determined to pursue Antarctic exploration in the interests of science and nationalism. Within this context, the NAE’s commission included not only collecting scientific samples but also attempting to claim the South Pole in the name of England.

Celebrity

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the quest for scientific knowledge drove many explorers and their supporters to mount elaborate polar expeditions. So, too, did the powerful forces of patriotism and adventure. Explorers from a range of countries who succeeded in mapping new territory or reaching previously undiscovered areas were hailed as heroes. The islands, bays, and mountains they reached were often named after their respective monarchs or sometimes even after themselves. And for the most accomplished explorers, scientific and geographic discoveries in far-off lands led to professional success, fame, and fortune at home.

Courage

Shackleton grew up in a solidly middle-class family whose ambitions for him focused primarily on his becoming a doctor. In his youth, Shackleton developed a fascination with the sea and English poetry. He was an avid reader of The Boy’s Own Paper, a British weekly published on Saturdays that promised “escapism, practical advice, [and] moral uplift” and was full of stories of naval lore. Later, he admired the work of the 19th-century poet Robert Browning, memorizing verses about manhood and heroism. From adolescence onward, he was enthralled by the idea of man mastering nature.

“For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Sir Edmund Hillary, first person to reach the summit of Mt. Everest

Looking Ahead

Explorers have always led the uncertain pathways to the unknown; to the future. Adventures, by definition, are characterized by unusual, exciting and typically hazardous experiences or activities; or ones that call for enterprise and enthusiasm. One does not have to be trapped in the ice floes of the Weddell Sea to have those experiences; just ask an entrepreneur!

I wonder, what are the confluence of factors that will produce the adventurers, the Shackleton’s, of the early 21st century? On which horizons will they explore?

Case notes are sourced from: Leadership in Crisis: Ernest Shackleton and the Epic Voyage of the Endurance, by Dr. Nancy Koehn, ©2003, President and Fellows of Harvard College

In Other Words…

“Equipped with his five senses, man explores the universe around him and calls the adventure Science.” ― Edwin Hubble

“Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised.” ― Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World

“I may say that this is the greatest factor: the way in which the expedition is equipped, the way in which every difficulty is foreseen, and precautions taken for meeting or avoiding it. Victory awaits him who has everything in order, luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time, this is called bad luck.” ― Roald Amundsen, led Antarctic expedition that was first to reach the South Pole, on 14 December 1911

“Robots are important also. If I don my pure-scientist hat, I would say just send robots; I’ll stay down here and get the data. But nobody’s ever given a parade for a robot. Nobody’s ever named a high school after a robot. So when I don my public-educator hat, I have to recognize the elements of exploration that excite people. It’s not only the discoveries and the beautiful photos that come down from the heavens; it’s the vicarious participation in discovery itself.” ― Neil deGrasse Tyson, Space Chronicles: Facing the Ultimate Frontier

“Emergencies have always been necessary to progress. It was darkness which produced the lamp. It was fog that produced the compass. It was hunger that drove us to exploration. And it took a depression to teach us the real value of a job.” ― Victor Hugo

In The Word…

“I can do all things through Him who strengthens me.” – Philippians 4:13